From the old catalog published of the manuscripts of the library. It is clear that the library of Ibn Hubeish contains six hundred and thirty-six manuscripts and letters, that is, its content is two hundred and thirty manuscripts, and seventy in total of four hundred and six letters. The oldest ownership of the manuscripts in the name of the Sheikh dates back to the year 1175 AH/AD 1761 This means that he started buying books eight years after he went to Egypt, when he was fifteen years old. A large part of his manuscripts were collected during his life either by purchase, where more than once the text ” moved by purchase to the Sheikh Mohammad Budeir”, or the reproduction, “written to Maulana the virtuous Sheikh Mohammad Budeir Hubeish Al-Maqdisi, resident in Cairo”, or the dedication and endowment “Waqf by the poor slave. Taha al-Tamimi is and its explanation is dedicated to the books of our master Sheikh Mohammad Budeir”

Distribution of manuscripts by subjects

| Subject | Number of manuscripts |

| Quranic Sciences | Eighteen titles |

| Interpretation | Fourteen titles |

| Hadith and its terminology | Fifty-six titles |

| Fundamentals of Religion | Fifty-seven titles |

| Sufism and Sharia Ethics | Ninety-three titles |

| Origins of Fiqh | Sixty nine titles |

| Fiqh | Fifty-six titles |

| Prophetic praises and Mohammedan prayers | Twenty-eight titles |

| Arabic Language | Fifty-eight titles |

| Arabic Literature | Ninety-five titles |

| History | Ten titles |

| Logic | Twenty-two titles |

| Miqat | Twenty-five titles |

| Mathematics | Nine titles |

| Medicine | Four titles |

| Miscellaneous Topics | Twenty-two titles |

| Total | Six hundred and thirty-six titles |

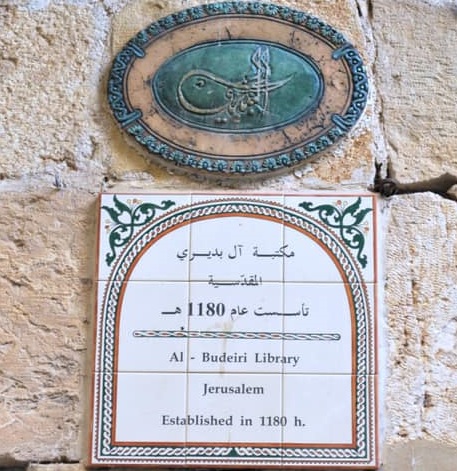

After the death of Sheikh Ibn Hubeish , his library stopped developing, growing or performing any service, and this can be seen from the second table, which shows the distribution of manuscripts by centuries. This reinforces the view that these libraries are due in their establishment to individuals who had the culture and interest in books and collected them, and their libraries became a kind of pride or ostentation. The role of these families became to guard these books in their places and prevent those interested from approaching their books. Let’s take as an example what Asa’ad Atlas wrote about the Budeirieh Library, (although I think this his personal opinion, and it seems that he did not ask any of the family members about the library, but was content with what people usually convey regarding things they know nothing about, especially in the East, where he said that, “Al-Budeiri is an ancient family of the oldest families of Jerusalem as well, and they had large safes rich in their manuscripts, but they shared them and dispersed them, and the largest of the manuscripts of these vaults are from Sheikh Mohammad Afandi Al-Budeiri, who kept them at Al-Aqsa Mosque.”

Distribution of manuscripts by centuries

| Hijri century | Number of manuscripts |

| Sixth | One copy |

| Seventh | Five titles |

| Eighth | eleven titles |

| Ninth | Twenty-five titles |

| Tenth | Seventy-five titles |

| Eleventh | One sixty-eight titles |

| Twelfth | Two hundred seventy-eight |

| Thirteenth | Sixty-four titles |

| Fourteenth | Nine titles |

| Total | Six hundred and thirty-six titles |

It is noted from this table that the number of manuscripts dating back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries AD is seventy-three manuscripts, of which fourteen manuscripts were copied in the first twenty years of the thirteenth century, that is, before the death of Ibn Hubeish , and fifty-nine manuscripts remain, which are likely to have entered the library after the death of its founder, and fourteen manuscripts were purchased by his heirs and five manuscripts were copied by Mohammad Al-Danaf Al-Ansari.

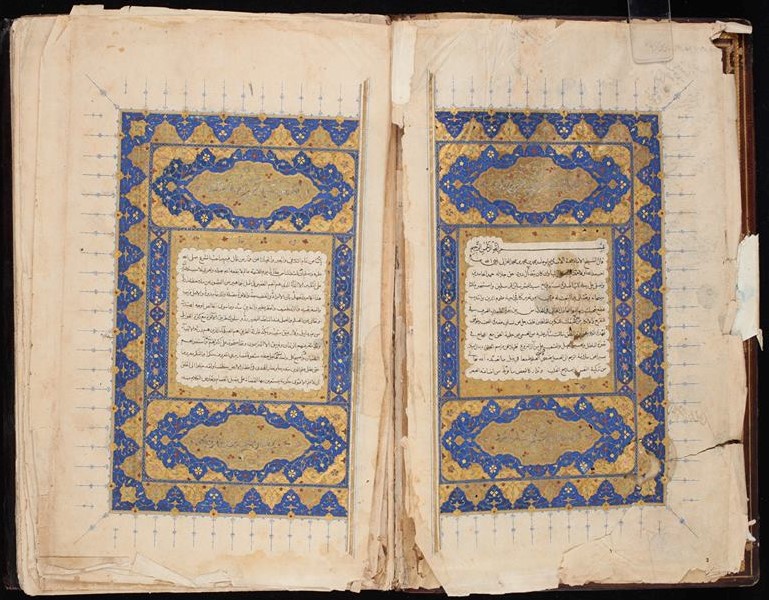

The oldest manuscript in the library is the ‘’Al-Rissala al-Qushayriyya’’ Which is considered as an indispensable reference book for those who study and specialize in Islamic mysticism by the author Abu Al-Qâsim Al-Qushayrî, who died in 465 AH/AD 1073. This copy dates back to 21 Rajab in 562 AH/AD 1167, and there are also five manuscripts copied in the seventh century AH, and the most recent manuscript is No. 102 and was copied on 16 Shaaban 1320 AH/AD 1902 and named ‘’Al-Isfar ‘an Nataij al-Asfra’’ Fluorescence results for fluorescence by Mohey Al-Din Ibn Arabi and copied by Mohammad Amin Al-Danaf Al-Ansari. It is noted that more than a third of the manuscripts were copied in the twelfth century in which Ibn Hubeish lived, the twelfth century AH. From the table we know that more than five hundred titles relate to religious topics and linguistic sciences, and that scientific topics are limited as well as logic and Miqat, and in general this applies to all libraries of that period.

The loss of manuscripts is one of the problems of private libraries where it is constantly observed as the loss of some of their collections, either as a result of damage, or theft, The loss of these manuscripts must be one of the basic and important motives that must push their owners to photocopy them, because with time they lose part of their contents, and digitizing preserves them. For intellectuals and future generations, and even if the original is lost, the picture shows us our cultural properties over the years, and preserves this wealth for future generations. The Hill University in the United States put forward a project to digitally photocopy the manuscripts of Jerusalem, where it adopted the manuscripts of the Budeiri Library, the Khalidi Library, the Isaaf Nashashibi Library, and the manuscripts of the Church of St. Anne and the manuscripts owned by the Copts have been digitized, and unfortunately the Awqaf, Armenians and other monasteries refused to work on their contents.

For several years, a volunteer committee from the Budeiri family (Adel, Ragheb and Shaimaa) has been re-modernizing and developing the library to bring it back to life for the sake of the interested public and the history of the city, because of the manuscripts it contains mainly. The committee has done a great job of reassembling the Dasht papers that usually accompany the libraries of Jerusalem Waqf, thus doubling the number of manuscripts of the library to reach more than one thousand and a hundred titles. This is a great work done by individuals who love the city and its heritage The committee should be thanked and praised for their work for all those who care about the city and its history

In the first edition of the index, the number of Al-Budeiri manuscripts was 665, while in the new index the number has doubled, thanks to the efforts made by the family committee mentioned above. In addition, they also found dozens of letters in various places of the library, with different manuscripts from different periods. that provide us with valuable information about the sources of some books. Now we also know that the father of Sheikh Mohammed Budeir was a buyer of books whose manuscript (No. 277) reads, “in addition to the endowment of my father Mohammad Budeir in 1232 AH/AD 1816”. The presence of many manuscript letters written in Moroccan calligraphy may also indicate that they are not the property of the father of the Sheikh, and that these copies may have been brought with him from Morocco, and therefore this collection formed the nucleus of the library on which Sheikh Mohammed built Al-Budeiri Library.

The Sheikh had an uncle named Hassan, Sheikh Mohammed married his daughter, and it seems that his father and uncle settled in Jerusalem, but we do not know when the Sheikh’s father and uncle settled in the city, was this done after his son was in Al-Azhar so he can be close to the place of study of his son?, or did he return to Morocco? and when his son completed his studies his father came to settle with him in the city? We know that his late father Budeir had died and was buried in Jerusalem, because in his objection to those who accused him of witchcraft, he points out that they scared his elderly father.

I place in the hands of esteemed researchers the third and most important index that I prepared for the manuscripts of some libraries in Jerusalem. This collection, which is owned by the Al-Budairi family, includes a number of important manuscripts. It includes six unique manuscripts and at least 26 rare manuscripts. It also includes 18 manuscripts that were copied in the author’s handwriting, and nine manuscripts that were copied. Preferably in the author’s handwriting.

The Badiri library includes other manuscripts that are not rare, but they gain great importance in terms of ownership, as some of them were in the possession of Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, Ibn Hisham al-Ansari, al-Murtada al-Zubaidi, Abdullah al-Sharqawi, and Ali bin Yashrat al-Tunisi al-Husayni, in addition to seven judges. There are seven manuscripts that were donated to mosques, eight to students of knowledge, and two to two schools.

We can trace the sources of this collection, which was established by Sheikh Muhammad al-Badiri and his sons after him, by means of the places of copying and the names of the owners. Many of these manuscripts were carried by the Sheikh with him from Cairo after his return to Jerusalem, and some of them were donated or gifted to the Sheikh by some notables, including Muhammad Pasha, the governor of the Levant in the year 1196, where he found the Book of Meccan Conquests. I refer here to the overlapping contents of Jerusalem’s libraries, where scholars and students of knowledge exchanged and borrowed books, and sometimes some of them were not returned to their owner for one reason or another. Therefore, we find in any Jerusalem library manuscripts transferred to another library.

The manuscripts of the Badiriyah Library vary in size. The largest is manuscript No. 175/154, copied in the ninth century, and its dimensions are 36.3-27 cm. The smallest one is manuscript No. 378/141, copied in the twelfth century, and its measurements are 14-9.8 cm.

It is noteworthy that many pages have been lost from some manuscripts, as they were numbered with a modern pencil. Examples of this include the manuscript “Al-Ibtihaj fi Ihtbir Al-Hawi wal-Minhaj,” from which eight pages were missing, and the manuscript “Part of the Treasures of the Needy in Praying for the Holder of the Banner and the Crown,” where they were missing. It includes three folios, and the manuscript “The Virtues of the Holy House and Hebron, peace and blessings be upon him, and the Virtues of the Levant” by Ibn al-Marji, whose pages were numbered with lead, and pages 78-97 and beyond page 117 were lost. There is a manuscript missing at the beginning and end, as its lead numbering begins with 21 and ends with 188, so I put it in the shower.

I divided the collection into three sections: the Qur’an, the individual ones, and the collections, each with an independent numbering, making up a total of 925 volumes on the shelves. The number of copies of the Qur’an was nine incomplete, containing 79 separate parts. The number of individual manuscripts reached 755 volumes, bearing 667 main sequential numbers on the shelves, where some numbers included several parts. The number of collections reached 91 volumes, containing 501 manuscripts.

I have made every effort to identify the titles and authors of the manuscripts that were not written by the copyists on the covers or whose first leaves were lost, as I reached them by comparing the manuscript texts with the printed books. When the contents of this index are compared to the manuscripts themselves, the researcher will find that the titles and names of the authors of dozens of manuscripts preserved on the shelves have been recorded. No titles or authors’ names. However, I did not find the titles and authors of a large number of the library’s manuscripts, and I placed those manuscripts at the end of each group separately. I also put an estimated title of the manuscript in parentheses ( ) in case you do not recognize the title of the original manuscript. I also copied several sentences from those manuscripts to make it easier for researchers to identify their titles and authors.

I have given separate numbers to the volumes of a single manuscript, because many of them were copied in different eras. In some cases, all parts were given one main number, for some comprehensive collections, such as Sahih al-Bukhari, which came in 60 parts.

Under the item (Content) I mentioned a description of the content of the manuscript. Under the item (Date of Copy), the Hijri year is mentioned, followed by the Gregorian year. In the event that the year is not known precisely, I estimated the Hijri century without writing the word “most likely.”

Under the entry (paper area), the length and width of the paper are listed, then (text area), i.e. its length and width. As for the cover entry, the word “missing” indicates the presence of a trace of a missing cover, while the word “none” means that the manuscript’s leaves were not bound at all.

Under the item (Handwriting), I mentioned the type of handwriting. If that item is omitted in the indexing of a manuscript, this means that its handwriting is usual.

The item (Tamleek) included some scraped tamliks that I was able to read, readings, and some related phrases.

Under the heading (Notes), other copies found in Palestinian libraries in particular were mentioned, as this makes it easier for local researchers to find additional copies instead of the trouble of searching outside Palestine. Regarding the letters appended to some manuscripts, which were both incomplete and unimportant, I skipped them and contented myself with referring to them. When describing the manuscript or cover as being in good or average condition, the description is relative.

Under the topic of poetry, poems with literary purposes were included, while systems of jurisprudence, Sufism, and others, each of them was included under its topic.

Entries that did not contain data such as naskh or ownership were deleted, and (content) was deleted for the sake of brevity and to avoid repetition if the title or the beginning of the manuscript included a statement of the content or subtopic.

The manuscripts are described under 1,177 sequential numbers in this index to describe a book or a letter. The number (349/43), for example, means that 349 is the serial number in this index, while 43 is the serial number of the manuscript on the shelf in Al-Zawiya Library. To locate a specific manuscript through indexes of titles, authors, and transcribers, the reference is to the serial number in this index, and not to the page number in this index or to the number of the manuscript on the shelf.

I also arranged the manuscripts alphabetically, according to the main topics, then according to the author’s nickname, then according to the titles of his works on the same subject. As for collections in general, each message was often described individually. When there were other copies of the manuscript with different specifications, they were described separately, immediately after the description of the first copy.

It is noted that most of the manuscripts of the Badiriyah Library are searched Language, jurisprudence, and Sufism, which are the areas of interest of the Sheikh, are distinguished from other Jerusalem libraries by the abundance of books on Shafi’i jurisprudence, which is the doctrine of the founder of the library.

The Al-Budayriyya Library includes four manuscripts copied in the sixth century, which are the Al-Qushayri treatise copied by Al-Mubarak Ali bin Abi Al-Qasim Yahya bin Saad Allah Al-Baghdadi in the year 562/1167, the fifth part of “Al-Shamil fi Branches Al-Shafi’iyyah” copied in the year 592/1196, and the sixth part of the Musnad of the Imam. Ahmad, which was copied by Abu Amr bin Muhammad bin Ghalib Al-Lakhmi in the sixth century, and a manuscript of unknown author entitled “A Book Containing Every Type of Wisdom and Literature, in Verse, Prose, and Other Things.” The first part was copied in the sixth century, then Ishaq bin Omar copied the rest of it in 635/1238.